The Visionaries, Madmen, and Tinkerers Who Created the Future That Never Was

MEN WHO PLAN BEYOND TOMORROW

Part of a series of articles on ad campaigns featuring futuristic inventions.

See also Pan-Am's Rocket Car, Super-Transport on Super-Highways, Quaker State's "Year's Ahead" Campaign, and New Departures of Tomorrow.

Men Who Plan Beyond Tomorrow (MWPBT). A maker, a doer, a dreamer, a creator of the future, with brains and brawn and taste. Possibly the greatest come-on ever devised to sell high-end whisky to the self-proclaimed sophisticated male who liked to think of himself at the pinnacle of American society.

The time was 1942. America had finally entered the war. Men by the millions were headed into service, about to be whisked out of the country. Those who were left tended to be older, past their physical prime perhaps, but still nominally in charge although they were increasingly being told what to do by the government. They wanted reassurance of their masculinity. How better to do so than to be apotheosized as the creators of the postwar world?

Seagram's was a Canadian firm, known for the innovation of selling whisky in bottles. Seems obvious today, but at the time most whisky was sold through intermediaries in barrels, which then could be cheapened and adulterated before reaching the public. Bottled whisky was a guarantee of quality. Seagram's also had a huge reputation because it sold massive amounts of whisky to Americans during Prohibition. It was legal to sell booze to Americans in Canada from 1920-1930: how they got it into the U.S. was their problem. Seagram's also suspected that Prohibition would be short-lived. After Repeal, it had the largest reserve of aged whisky in the world. They even launched a "drink moderately" advertising campaign in 1934 to align their whisky with sipping graciously rather than the drunken excesses of Prohibition. As a blended whisky, Seagram's taste never varied. If you liked it once, you always would.

Seagram's basic whisky was Seven Crown, progenitor of the classic 7 and 7 highball, classically composed of 1.5 oz. of Seagram's Seven Crown, 5 oz. of 7 Up, and a slice of lime, over ice. Their premium product was Crown Royal, created in 1939 for the first visit of a British reigning monarch to Canada. Unfortunately, Crown Royal wasn't available in the U.S. until the 1960s. That left V.O.

V.O., which in the public fancy stands for "Very Own," although nobody actually knows its origin, was launched in 1914 when Thomas Seagram asked the Seagram's Waterloo Distillery for a special barrel of whisky for his wedding. He liked it so much that he marketed it as the firm's flagship product.

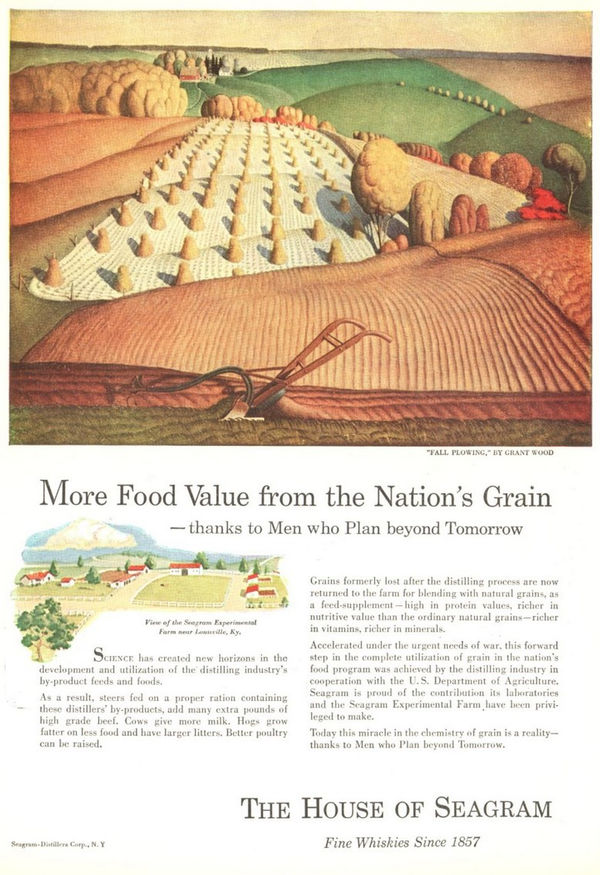

The war disrupted everything. Seagram's - which did most of its business in the United States - immediately moved into super-patriotic mode with a series of a posters of the "loose lips sink ships" variety, of which my favorite is this caricature of Hitler funneling in loose talk through his ear.

Patriotic posters had one tiny fault: they sold no whisky. All the ad agencies spent the first half of 1941 frantically brainstorming campaigns that wouldn't offend the public but encourage them to spend their war wages on product. Seagram's was luckier than, say, car companies, in that they had product to sell. Everybody drank during the war. Success merely meant nudging consumers to drink the more expensive varieties.

The first ad appeared in July 1942. The headline was the clunky "Men Who Think of Tomorrow Appreciate Seagram's Foresight!" The futuristic detail soared above the page: an illustration of a sleek flying wing flying over clouds.

The superplane of the future - shooting through the stratosphere at a thousand miles per hour. You'll breakfast in New York and lunch in London ... or jump from Boston to Borneo between dawn and dusk. And all because there are men today who think and plan for Tomorrow.

Wait, they both think and plan for tomorrow? The imagery of the peripatetic traveler for whom time is money is good, but the presentation is also clunky.

The connection with Seagram's? Merely that they've been aging the whisky now found in their bottles seven years ago. They thought and planned for the future and you, you lucky whisky driner, will reap the benefits.

Five more similar ads appeared before the end of the year. One didn't even have any futuristic technology, merely a plea to buy war bonds and stamps because the statesmen of the United Nations were planning for the world after the war. This is 1942, remember. The United Nations were the Allies, not the organization that didn't yet exist. Here's a gallery of those five ads.

Not until the first ad of 1943 did the copywriters hone their pitch. The headline changes to "Men Who Plan beyond Tomorrow" - note the nicety of not capitalizing the preposition even if not doing so seems like a typo - and the copy emphasizes the future technology.

Perfected Television and radio telephone combined! You can sit in your Chicago office ... talk by radio phone to your representative in London ... and see him during the conversation. Or you can flash on your screen the face of a friend in China. That's only one of many wonders being developed now by the Men Who Plan beyond Tomorrow. [Ellipses in origin. Please don't ask how the finicky copyeditor allowed that capital T on Television.]

No doubt here who the audience was. Didn't every silver-haired businessman dream of far-flung deals with representatives all over the planet? Or of being a cosmopolitan with friends in exotic locations while he rules the roost from his high-tech headquarters? Those at the top of pyramid drank only the best and those in the middle aspired to be like those at the top. Seagram's V.O. was their reward for the long hours. Remember, Seagram's aged its finest whisky for six years! Even Seven Crown was aged only four years.

(Six? If older is better in the whisky world, what happened to that seven year blend of 1942? A voyage through Seagram's ads of previous years is a dizzying procession of numbers going up and down as fast as the stock market. In a 1937 ad, V.O. was aged six years, but Seagram's Pedigree was aged for eight. In 1939 V.O. stayed at six years, while both Seven Crown and the lower-end Five Crown were aged "4 or more years."A 1941 ad said that Seven Crown was a mix of five and six-year-old whiskies. A Christmas ad in 1942 for the full line of Seagram's whiskies (Pedigree vanished after 1940) slipped V.O.'s change to six years in the fine print. Seagram's may have thought and planned for the future but they didn't see a world war coming.)

The rest of 1943 saw V. O. ads appear about once a month in prestigious magazines like Life, Time, Newsweek, Esquire, and Collier's.

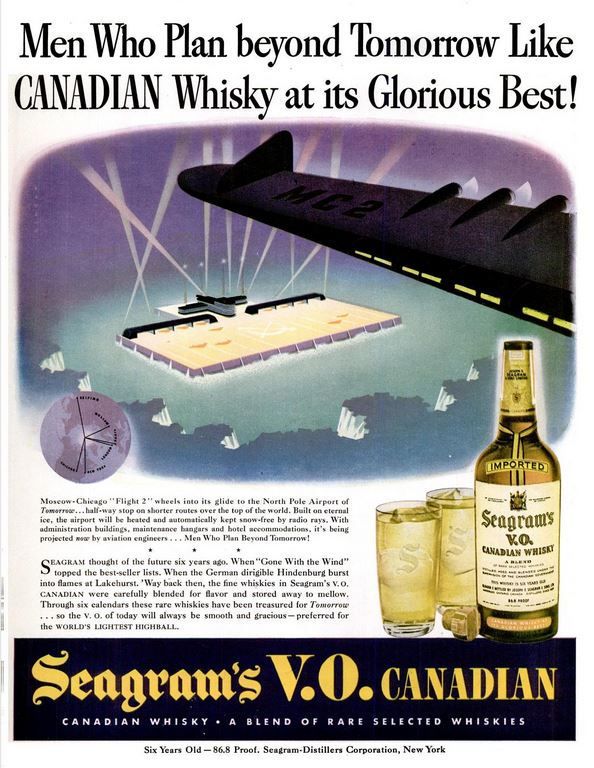

These visions of the future are squarely in the mold of contemporary predictions: a Corbusian cityscape with amphibious car-boats; a rotating house with a personal airplane in the driveway; 3-D movies, rocket ships. And then there were the conveniences for the middle-class lifestyle of the future. Helicopters for suburban commuters. A North Pole airstrip to shorten travel by using a great circle route. A giant cruise ship. The future would be pretty, gracious, full of ease and comfort. Lean back, sip some whisky, and enjoy contemplating it.

Seagram's turned to Joseph Binder (1898-1972) to do the art for the early years of the campaign. (The style changes after the war and I haven't determined who the artist was then.)

Binder, a native of Vienna, entered the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts in 1922, becoming a master lithographer. Two years later he founded Vienna Graphics, a graphic design firm. Influenced by the Cubist and DeStijl movements, Binder broke pictures down into geometric patterns and contrasting colors, gaining an international reputation as a poster maker.

He moved to America after taking first prize in competitions sponsored by the the Art Directors Club of New York and the Museum of Modern Art and also winning a competition for poster designs for the American Red Cross, which hired him in 1936. Dozens, possibly hundreds, of posters and magazine covers followed before he turned to painting in the 1950s.

The original art for the MWPBT series sells in the neighborhood of $10,000 today at auctions. Here are two examples from the 1943 campaign.

1944 was a repeat of 1943. Seagram's customers might be suffering from wartime shortages but there were no shortage of dreams of a better future. Some predictions were better than others. Any contemporary physicist could have told them that using giant vacuum tubes to collect and energy from lightning bolts was a non-starter. Supermarkets with massive parking lots were to fit into suburban lifestyles better than door-to-door trailers of food exposed to the outdoor air. Fax machines built into television sets never replaced newspapers. Sleek electric kitchens surely did arrive, however, and so did fighting fires from the air by dropping chemicals on them.

The war may have ended in 1945 but the MWPBT campaign must have been successful because it continued throughout the year. The only change was a slight alteration in design to add thumbnail picture under the main splash.

Predictions were a touch bolder than those of 1944. "[O]n your car's dashboard, instruments will signal changing traffic lights and other warnings on the road ahead." "Face-to-face conferences through television will be held coast-to-coast... Records will appear as if by magic from files automatically operated..." "[Railroad cars], lighted by cold cathode, will be air-conditioned and cleansed of dust, smoke and odors by static electricity." "near the curb a moving sidewalk, on the conveyor-belt principle, will speed 'through traffic,' eliminate jostling and allow strollers more freedom."

Seagram's ad company must have planned out campaigns by calendar years, for 1946 brought another new look, although the layout changed several times during the year. Some of the art looks distinctively difference from Binder's use of blocks of color.

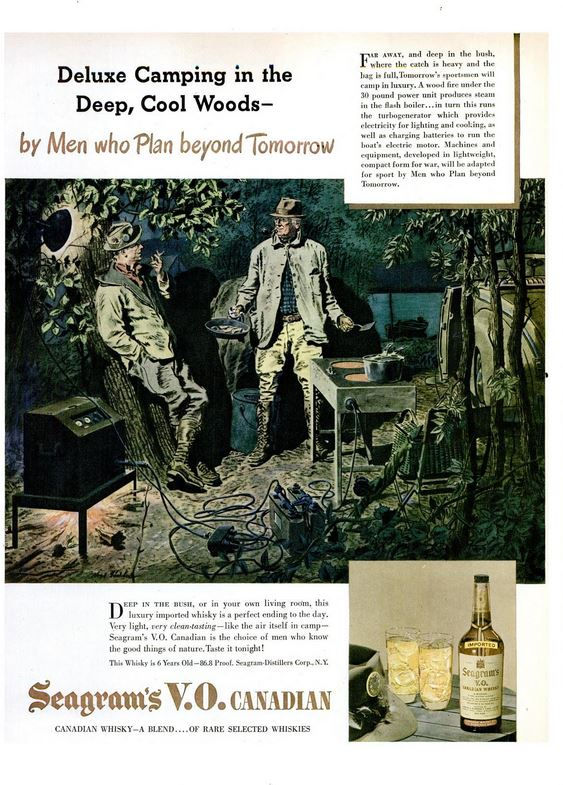

Predicting a sports bar full of televisions showing the latest games - in full color - hit the bulls-eye. Even niftier color schemes were featured in an amazing plantation where dye was injected into the roots of cotton plants, growing out in a pastel rainbow. The executive of tomorrow would have marvels at his fingertips. Personal radiophones keep him in touch with the office from the golf course and his dictaphone will type out his memos through voice recognition. Camping becomes luxurious with a turbogenerator. And no more bundling up for those fall football games. "Tiny particles of heat-reflecting metal" sewn into the fabric of his suit (yes, he will still wear a suit to a football game) will keep him warm without a topcoat. (I can't explain the low-life wearing a hoodie.)

The ad at the top of the page is supposedly also from 1946 but I can't find it in any magazine. If you can provide a date and a source, please us the Contact page to let me know.

1947 saw another change in design, but the essentials were still there. Inevitably, atomic power used for good was one of the predictions:

Harnessed atomic energy will transform deserts into rich fruit and grain country... provide power to tap subterranean water for irrigation, power to run machines to operate utilities. Already Atomic scientists are adapting the world's newest wonder to this peacetime use. [ellipsis in original]

I wonder what Atomic scientists (there's that weird capitalization again) the copywriter was talking to. Never get your science from the Sunday supplements.

The weirdest prediction was that of using a maple-leaf shaped sail to spiral cargo gently down to earth. But some light planes today do indeed have parachutes.

That's about par for predictions. The world of tomorrow can take an awful long time to arrive.

The future stops halfway through 1947, but, surprisngly, the slogan didn't. For the rest of year and into 1948 and once in 1949, ads featured luxury and elegance, brought to you now by The Men who Plan beyond Tomorrow. (Bet they didn't plan on losing the capital W in who. New copyeditors, maybe?)

Some of the ads so emphasized now that they slipped into the past tense: "Styled for a great occasion ... by Men Who Planned beyond Tomorrow." (Wait. A capital W? They're just messing with my head now, aren't they?)

The Future had caught up with the times. Why look to possible technology when you could luxuriate in today's pleasures?

The 1950s were to be good for Seagram's as it built into the world's largest vendor of alcoholic beverages in the world and the head of a giant and diverse conglomerate by the 1990s. Ironically, the company couldn't foresee its own future. The company was broken into pieces and sold off. The brand name remains and so does a revived V.O. but the company is probably known more for its flavored malt beverages and hard seltzers. Seeing Seagram's Escapes Calypso Colada in its future would have been the true triumph of clairvoyance.

November 26, 2019