The Visionaries, Madmen, and Tinkerers Who Created the Future That Never Was

EDISON BELL, YOUNG INVENTOR

Boy geniuses are all over children's literature. Tom Swift is by far the most famous name in the field today, thanks to five generations of Toms stretching a century from 1910 to 2007. The fifth series, six books from 2006-2007, are called, bluntly, Tom Swift Young Inventor.

The original Tom Swift wasn't all that original, though. He followed very closely in the footsteps of Frank Reade, Jr., a sixteen-year-old inventive genius, who traveled the world with his wonderful toys for 191 weekly issues of the story paper Frank Reade Library, from 1892-1898 and 96 reprints in the Frank Reade Weekly Magazine from 1902-1904. Almost all of these were written by the speed legend Luis Senarens. Frank Jr. appeared 28 times in earlier magazines, starting in 1882. There was a Frank Sr., as well, created by Harold Cohen in 1876 for the story paper Boys of New York. And Frank Sr. was a very direct rip-off of Johnny Brainerd, the hero of The Steam Man of the Plains, by Edward S. Ellis, in American Novels #45, August 1868, an early dime novel. Ellis, meanwhile, copied his steam man, a ten-foot-tall wagon-pulling robot, from newspaper accounts of a steam man built by 22-year-old Zadock Pratt Dederick in Newark in 1868. Much more than this direct line exists. The success of the various series naturally inspired other publishers to start their own. Frank Reade, Jr. competed with Tom Edison, Jr; Tom Swift with the Young Engineers.

It's a truism in the industry that stories about teens actually get much of their readership from younger fans who aspire to their adventures. I know I started reading Tom Swift, Jr. and the Hardy Boys around the age of 10. By sixteen I went on to adult mysteries and science fiction.

That doesn't leave much of a niche for pre-teen inventors, who'd be a hard sell in any case. Who'd believe that a kid could create amazing, advanced inventions and battle bad guys around the country or even world? The answer was much the same as any other kid variant of an adult genre. Narrow the world to a neighborhood, put in friendly adults, turn the battles into hi-jinks, and definitely make the kid cute. Put those together and you might have a hit.

In 1940 comic books were the incredible hot sensation of the publishing world. Driven by the likes of Superman and Batman, individual comics were suddenly selling a million copies a month. Every publisher wanted a piece of that action. Titles sprang up by the dozens, with writers and artists throwing every idea that passed through their heads onto the four-color presses. Nobody knew what worked or didn't, but there was plenty of room for experimentation. A comic gave a kid 64 pages for a dime and strips were generally only a few pages long. Some comics had more than a dozen in each issue. Sales figures and letters that the huge buying base sent in decided a strip's fate.

Novelty Press, a small offshoot of Curtis Publications, a major magazine publisher, got into the game in June, 1940 with a single title, Blue Bolt. Unless you are deeply into vintage comics you have never heard of Blue Bolt, the Human Lightning Streak (though aficionados will note the famous team of Joe Simon and Jack Kirby created him), or any of the others on the cover: Sub-Zero Man, Sergeant Spook, Superhorse, Phantom Sub, and Dick Cole. Or the unsung Page Parks, Old Cap Hawkins, Pony Tracks, and Runaway Ronson found by flipping pages. Edison Bell, Young Inventor got a mere three pages somewhere in the middle, despite having the most nostalgically patriotic name scientific imaginable.

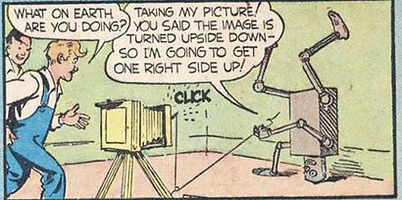

The story couldn't be more white bread middle America. Our hero, Eddie, is sent by his mother to the store for a pound of lard. What red-blooded young America genius would think this is fun? If you imagine Eddie is going to disobey, go find a different comic. He meets his friend Nicky there on a similar errand and they get to thinking. "Why can't we make a boy robot to run all our errands?" They run home and get to work. A box, some copper piping, and a Leyden jar later they have a robot they call Frankie, Frankie Stein. Presumably having seen the movie they know what to do next. When a storm blows in, a lightning bolt brings Frankie to life. By the next morning he's in the kitchen making breakfast for the family.

The neatest part of Edison Bell stories were the table-top projects that the kids at home could do to follow along with the inventions that Eddie makes. Even though the stories would shrink to a minuscule two pages in the future, they never failed to include a project.

Art for Edison Bell was provided by Harold S. DeLay. He had been an artist for 40 years, with a number of prestigious projects in his past, including illustrations for an L. Frank Baum novel. He did a bit of everything but probably had fallen into hard times during the Depression, as with so many other artists, and descended the prestige ladder to doing covers for pulp magazines and comic strips. Comic databases don't provide any script credits for the early issues, though, so its possible he was just a freelancer doing a quick job for a buck.

This is backed up by the noticeably different art in the second issue has, which has a somewhat older Eddie as well. The art credits for this and the next four issues shift to Harry Ramsey, who was just starting out as a comic artist but would stay in the field for two decades. Eddie creates a new metal alloy, subjects it to high-frequency radio waves, and gets a paint that makes things invisible because of x-rays. You read that right. The paint is even more miraculous than that. When his friend, now named Jerry, wears pants painted with Eddie's invention, the entire lower half of his body vanishes.

In Blue Bolt #3, Eddie is himself again, and I'm guessing that DeLay had a hand in it. Having conquered x-rays, Eddie is inspired to split the atom. It takes him just one panel to invent an atomic-powered rocket car, which leads immediately to a hope for rocket mail. I love this kid.

Sure enough, the do-it-yourself project is a rocket car.

In issue #4, Frankie helps rescue a wrecked train than Eddie and Jerry comes across while taking the rocket car for a spin by plugging himself into a telegraph line and sending Morse code. Soon, though, the inventions cease so that gadgets more in touch with the everyday world, like dictaphones and cameras, are made the focus. Then the invention angle is pretty much dropped so that the threesome is sent on Frank Reade Jr. style world adventures, longer and with issue-to-issue continuity. The image at the top is the first cover that featured Edison Bell. He's obviously older in these episodes but after the war starts is regressed to being a younger kid again, busy with the war effort and furiously hating the Axis.

The pre-war younger Eddie best features Frankie Stein, the cute talking pal that every kid would love to have. Imagine bringing your imaginary friend to life.

Comic historians give Ray Gill script credits for many stories after issue #10 as Eddie's age yo-yos. The more worldly the adventure, the older Eddie had to seem. Back at home, he remained a pre-teen. In Blue Bolt #33, February 1943, the project is a doll marionette, as far away from an atomic rocket car as can be imagined.

The Blue Bolt comic lasted an astounding 101 issues, until September-October 1949, with an Edison Bell story in each. By the end Edison Bell had long since lost the Young Inventor subtitle. In issue #88 his science fair project entry is an aquarium. He still foils bad guys regularly, but the charming innocence and inventiveness of a boy genius is fitfully rendered and often lost. So is Frankie Stein. That wasn't quite the last we see of Eddie, though. As did most comics publishers, Novelty Press (which in 1949 sold all its titles to Star Publications) spread strips across several titles. Edison Bell appeared in the short-lived Dick Cole and every issue of 4Most, which later became 4Most Boys, a neat title pun. 4Most Boys #40, April-May 1950, appears to be Eddie last appearance. He's back to being quite young and knickered, but still manages to get a job in a bookstore, surely breaking some child labor laws. From this hardly adventuresome position, his brilliant brain tips off the police to a bank robber, using an ingenious book title clue. That was the last issue of 4Most Boys and Star didn't bother to move him around again.

With around 150 appearances and dozens of fun-to-do projects, Edison Bell should be a better remembered comics character than he is. The young inventor fell into that in-between world, not a superhero, not a cuddly anthropomorphic animal, that filled pages but never became stars. Nevertheless, I'm putting Edison Bell and Frankie Stein high in my roster of roboteers of the 20th century.