The Visionaries, Madmen, and Tinkerers Who Created the Future That Never Was

GOING... GOING... GONE

On July 12, 1936, the Chicago Tribune printed what might be the greatest paragraph in the history of news.

Interest in television turned later in the week to what might be called invisibility rays. Prof. Gosztonyi of Budapest has a machine - he's demonstrated it - that makes people seem to disappear. Harold J. W. Raphael of London has another machine that makes inanimate objects disappear. In one demonstration he caused a radio set, a tin of cigarets, and a clock to fade from sight. Raphael's machine is the invention of Prof. Stephen Pribil, a Hungarian. Prof. Gosztonyi is also a Hungarian.

Dueling Hungarian invisibility machines! Does it get more wonderful?

Down the rabbit hole we go with professors who aren't professors, rays that aren't rays, and invisible objects that aren't invisible even though people really and truly disappear before your startled eyes! The exclamation points are necessary. This story has it all, including a kidnapping, patents, a razor blade king, and battleships.

We start with a story in the October 20, 1935 American Weekly. A syndicated weekend supplement that was included in scores of big-city newspapers, The American Weekly boasted "Greatest Circulation in the World." Undoubtedly true, which meant that it was the greatest publicity machine in the country. Since, as the saying goes, nobody ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the American people, The American Weekly was a tabloid running sensationalist junk, living off of gossip, scandalous behavior, weird facts, scary warnings, and funny animals. Other headlines in this issue included "Charges Father Sold her for $125," "When Death May Lurk in Your Bird Cage," "Her Love Born in the Shadow of the Electric Chair," "Confessions of a Fashionable Drug Addict," and "A Real Rubberneck Man." And also the one we're interested in.

The "Vanishing Lady" Who Couldn't be Brought Back

"It is impossible!" Cried the Inventor, and Almost Went Crazy;

"Kidnappers!" Shouted Her Rich Papa; the Police Couldn't Fathom the Mystery --- But It Turned Out to Be Just a Brand New Way of Eloping

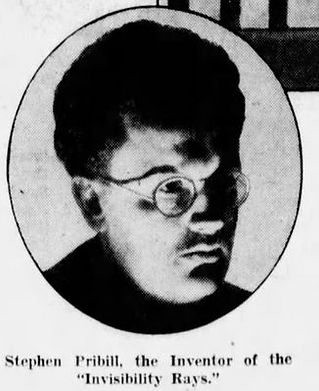

"Professor" Stephen Pribill - the article is honest enough to admit that the appellation was bestowed upon him by his press agent - was in the middle of his act at the City Park Theater. Pribill was an electrical engineer who claimed that "his invention is not a trick with mirrors, but a real discovery about light rays." He stooped to the unorthodox approach of exhibitions merely to raise money for further experiments.

No question that Pribill had a showman's flair. To reassure his audience, scattered through an almost empty theater, he first vanished and brought back a dachshund. Then a burly farmer volunteered from the audience, first handing his wallet and watch to his wife, a nice touch of doubt. Pribill "shifted some levers" - note that no apparatus is shown in the pictures accompanying the article - and he too faded out of sight and returned huge and whole. Both the dog barked and the farmer spoke while invisible, proving they hadn't been whisked through a trap door.

Esther Kiraldy, a seventeen-year-old-beauty, was next. She proved a willing, even eager volunteer, ostensibly because she had made a bet with her father that a useful purpose could be found for an invisibility machine. Pribill vanished Kiraldy and asked her to speak from the "void." Silence. He walked over and passed his hand over the chair where she should have been. It met no resistance.

"I will go verruckt, crazy, if I don't find where she went!" [Pribill] cried, clutching his hair.

"Also you will go to jail," prophesied the father.

The police came and started their investigation. Pribill had no assistants and nobody had been backstage. His consternation was real. The trick was all the girl's. So she said.

Kiraldy was in love with a young man named Paul Peterfy. She was desperate to escape her parents' smothering control as evidenced in a planned world trip the family was to embark on to ensure that the love-birds couldn't get together. A girl friend gave her the idea. They had appeared on the stage of the theater the year before in an amateur theatrical production. The back wall had a hidden door; the girl friend noted that apparatus was directly in front of it when she attended an earlier Pribill exhibition. When Kiraldy "vanished," she walked through the door, out the back entrance and into a taxi Peterfy had waiting for her. They whisked off by train to an elegant hotel in Vienna. One phone call later, the defeated parents acknowledged she had won her bet. She and Paul returned to Budapest, and Pribill was best man at their wedding.

You can't get a better story than this. Exactly why not a word of it is believable. The invisible hand of the press agent looms over every detail. He even writes himself out of the article so that Pribill can't be suspected of having an accomplice. The story is so much of a story that the trick door forms part of another story, the March 12, 1974 episode of the classic tv impossible-crime solver Banacek, entitled "Now You See Me, Now You Don't." As publicity, though, it's first rate. The yarn spread Pribill's name all over the world.

Assuming that really was his name. One of the odder facts about newspaper reporting before WWII is that names, especially of non-Americans, regularly got printed with variant spellings. Our inventor's name was given as Stephen Pribill, Stephen Pribil, Stephan Pribil, Stefan Pribil, Stefan Pribill, and Stevn Pribil. Maybe none of these were correct. The first few mentions of his invisibility ray in February 1935 give his name as Etienne Bribil. Etienne is the French version of Stephen and Bribil could simply be a typo, but the accounts that appeared in British and French newspapers are clearly write-ups of a press release and it's odd that his name would be misspelled in his own product. I'll use the form Stephen Pribil because that's how it's spelled on the two official documents I found.

In any case, there's no doubt that Etienne Bribil and Stephen Pribil are the same person. A Reuters news syndicate article, datelined Budapest, started the ball rolling (1935-02-15 Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail p.6).

A young Hungarian inventor, M. Etienne Bribil who is only 24 years of age, claims to have discovered a ray before which a marble statue becomes invisible to the eye.

He gave a demonstration of his invention to a representative of the paper "Budapesti Hirlap," who tells how, after the rays had played on the status, it slowly "disappeared."

But when the newspaperman put his hand where he had seen this statue, he felt it. Under further "ray treatment" the statue reappeared, he says.

M. Bribil refuses to divulge the secret of his invention, but he proposes to give a demonstration before experts.

How convincing the demonstration was can be seen in a May 1935 story from a Scottish newspaper (1935-05-11 Dundee Evening Telegraph p.8 )

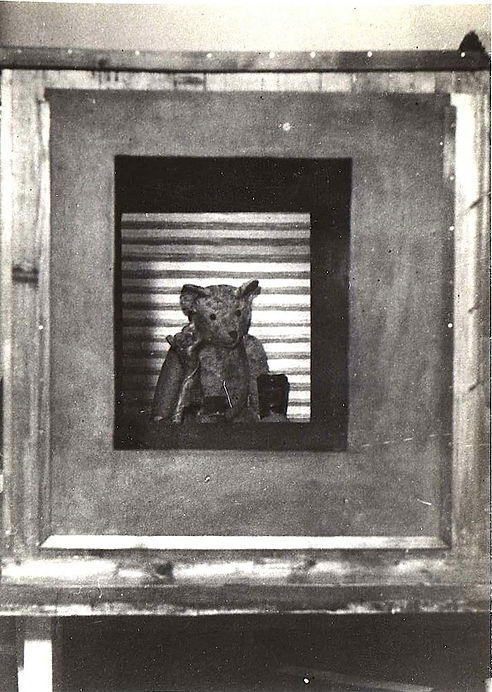

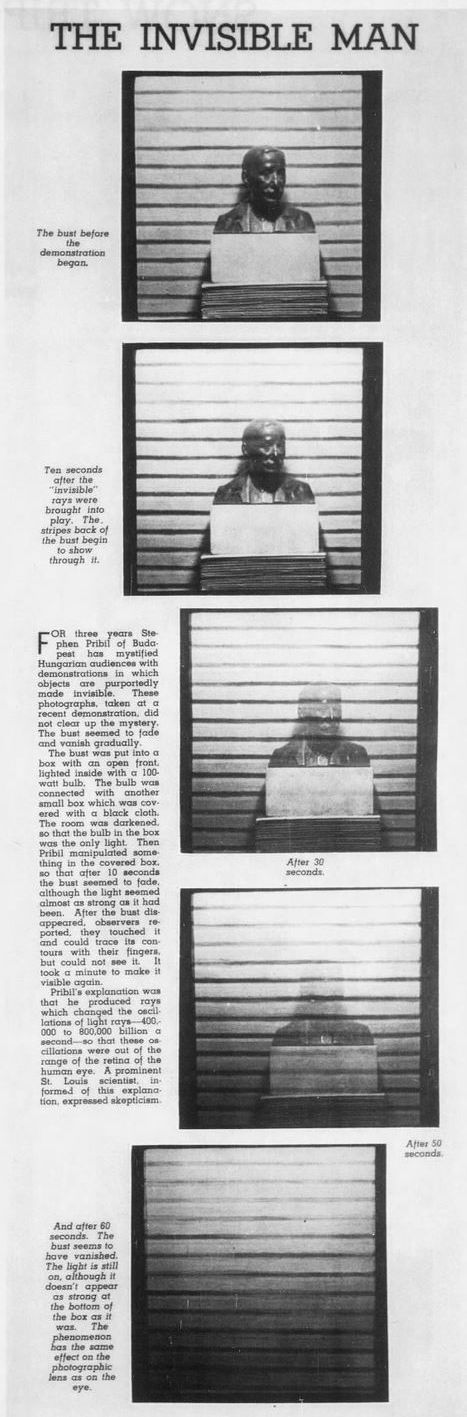

[Mr Pribil] can make objects of stone, metal, textiles, wood, a human hand, in brief, any object whatsoever, entirely invisible by placing them inside a specially prepared box which is connected by wires with an electrical apparatus which the inventor operates.

By switching on a current the exact qualities of which Mr Pribil does not yet care to divulge, the tangible objects within the small box of which the front has been taken out, stage-like, gradually fade away and finally become entirely invisible.

One may touch the objects during the operation and convince oneself that they actually are in their place, but the hand that touches them within the box becomes invisible at the same time.

For the demonstration, Mr Pribil places a box rather like a plain radio chassis on a table. The box is open in front and a curtain of gaily striped material, with horizontal stripes of various colors, forms the background.

Into the box are placed objects of any description and any material. They may come out of the pockets of the skeptically minded audience, to prove that they have not been specially prepared in advance. A couple of electric wires lead from the demonstration box to another box, placed at some distance from it.

It is behind this second box that the operator takes his seat, pressing mysterious buttons and pulling intricate little levers. In broad daylight, the outlines of the objects within the demonstration box become dim and blurred.

The stripes of the background curtain seem to cover the Teddy bear or the metal statue placed in front of it. The bear, the statue, or the hand of the skeptical spectator seem to melt into the background, and in another moment they have vanished entirely,

The incredulous onlooker puts out his hand to grasp the invisible objects. There they are sure enough, as tangible as ever, but look as close as you will you cannot see them.

It looks like a magician's illusion and that's what Pribil wanted to sell it as, valuable to stage tricks or advertising rather than an element of warfare.

The closest we ever come to an explanation for the rays appears in a tiny article from the Havas syndication (1935-12-30 New York Daily News p.12) when Pribil traveled to London to show off his device in late 1935.

Dr. Pribil, it is said, stumbled on the ray by accident while experimenting with mercury vacuum lamps in his Budapest laboratory. He noticed certain objects became blurry in appearance and then faded entirely from sight when subjected to rays whose exact nature he has not yet been able to determine.

How convenient.

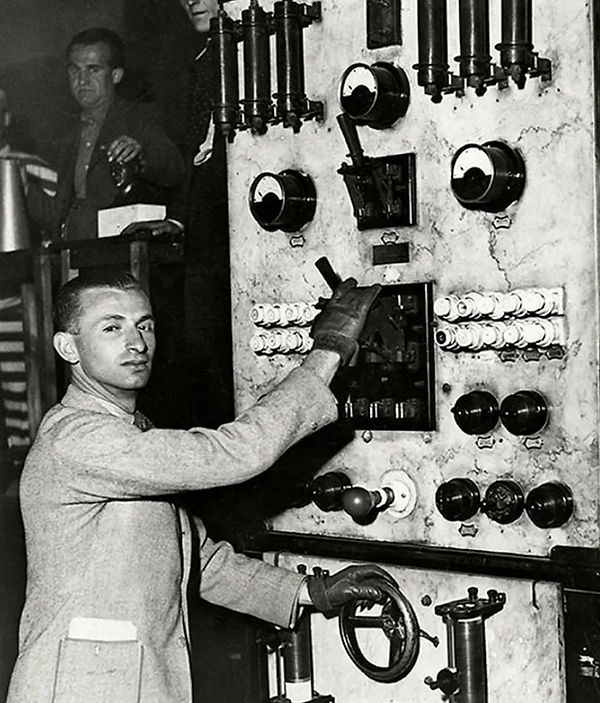

The London newspapers syndicated articles all over the world. The operator behind the website Jot101 found pictures from the photo archive of the Buenos Aires paper El Mundo, dated April 1, 1937.

According to the typewritten labels on the back of each photograph Pribil placed three objects — a teddy bear, a bronze statuette and an opaque china vase — in his apparatus — basically a wooden box fronted by a picture frame behind which is a sort of slated affair. Out of the back of this box electric cables are connected to a supply.

Excitingly, one of the photos shows the actual box, complete with teddy bear, and another has a portrait of Pribil himself, sitting behind a box with two cables trailing from it.

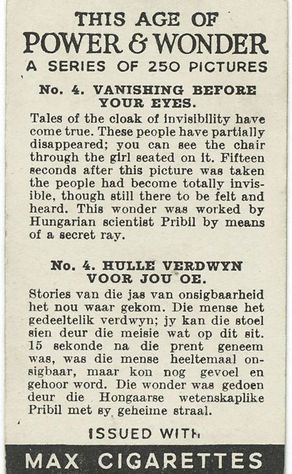

Newspaper coverage alone doesn't determine familiarity. Readers might have marveled at an article and completely forgotten the protagonist's name by the time they turned the page. All decades are full of nine day wonders. Pribil was an exception, an ongoing national sensation in Britain. As I continually note in these articles, a historian can tell how familiar a name was by its use in popular media and humor, where instant recognition is crucial. Pribil's fame is proven by, of all things, a cigarette card.

See companion page on the Max Cigarette card series at This Age of Power & Wonder.

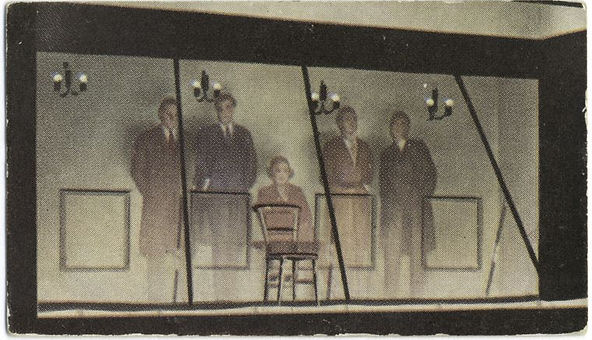

Cigarette cards were incredibly popular in England, with over 5000 series of cards issued. They covered every conceivable subject that the public might be interested in. By the 1930s science and technology were hot topics. The 250 cards in This Age of Power & Wonder series were issued between 1935 and 1938. Pribil made card #4, which means he made an immediate splash in the public consciousness. So popular was he that Max came back to him with cards #129-132. The vanishing man at the top of the page appeared on cards #130, 131, and 132. Card #129 was reserved for a portrait of Pribil himself, one of the few modern scientists to have his likeness in the series.

If this is the apparatus then what was the box with wires in El Mundo?

The artist's rendering certainly was taken from a image of the full apparatus. Perhaps Pribil found that the giant radio-transmitter-like box was too much to pack for transatlantic travel.

Pribil bounced from Budapest to Vienna to London as a young mystery genius for a full year before the unthinkable happened. A rival inventor popped up, courtesy of a insouciant columnist.

The between-war years were the Golden Age of newspaper columnists. Looking back it feels like New York City alone had 5000 of them, ranging from semi-serious to gossipy to complete goofballs. Among the latter was George Ross of the World-Telegram, whose "In New York" column was so breezy that it reads like communications from Mars. The tone didn't matter. Just being mentioned in a New York column was the exemplar of the notion that all publicity is good publicity, and it worked nationwide through syndication.

So when in July 1936 Ross published these paragraphs of amused gibberish he wrought unto the world a press agent's dream.

A man came in to ask, "How would you like to disappear?" First, I thought it a form of criticism and answered him accordingly. He didn't back out, but instead, explained that I had him wrong. He was only here to arouse my columnistic interest. McGuiness his name was and he represented an instrument called the Ray Z-67 that makes any human being or object vanish; that can create an Invisible Man. An Adam Gosztonyi, a Hungarian playwright and pamphleteer, but not a scientist, had invented it as a hobby.

So I went along quietly to have myself dissolved into nothingness. There was the machine in wood and crude iron, resembling nothing else except a giant washing machine. I was led onto a broad platform bathed in lights. Someone set the machine buzzing and Mr. Gosztonyi fooled with a set of ultra-violet rays. The illumination remained as bright. Out front, I heard a witness murmur, "He's going." Suspicious of both the Messrs. McGuiness and Gostonyi [sic], I, nevertheless, stayed pat. Then my friend's voice again, "He's gone." So I insisted upon being restored to human vision. My friend tells me that I vanished like a vapor.

The Ray Z-67, I'm informed, will soon be shipped to various amusement parks about the country.

You'll not, I trust, be surprised that no one ever referred to the "Ray Z-67" again. One poor befuddled reporter, however, ascribed a "Ray Y-67" to Pribil. Don't ever make the mistake of thinking that newspapers were better in the past.

Adam Gosztonyi was a real figure, not a nitrous oxide product of Ross's. (It's interesting to note that every newspaper agreed on the spelling of Gosztonyi - barring the occasional typo as above - a far more difficult name than Stephen Pribil. My guess is that reporters made sure to ask the correct spelling from Adam but simply assumed they knew how to spell Pribil. Personally, I'd fire a press agent who couldn't get my name spelled correctly every single time.) Ross got one fact correct, or as close to correct as Ross ever got. Gosztonyi, born in 1897, had indeed written a play, The Chameleon, produced at the Masque Theater in New York in 1931. He wrote his first book in Hungary in 1919 shortly before he moved to America. His being a "pamphleteer" is harder to parse. What I think Ross meant was that Gosztonyi spent the 30s writing adventure stories for a Hungarian publisher called World City Books. These were issued as small 64-page books about the size of a paperback. Google Translate results are hit or miss. Bloodthirsty Jack's Dust could be a rousing western, In the Footsteps of the Fox a crime thriller. Slim falls into a stack ... at least has an action verb in the title. I have no idea what to make of Street Familiarization, though. He ended his career as a script writer for the Hungarian Service of the Voice of America before dying in 1955. Ross did accurately say that he wasn't a scientist. How he got connected with an invisibility machine is a mystery.

A few days after Ross' column appeared, the battle between Goszyonyi and Pribil hit the headlines (1936-07-14 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette p.24).

Invisible Ray Battle Looms

Inventors Fight Over Gadgets

There's a battle of invisible rays in the offing.

Recently Professor Gosztonyi, Budapest inventor, demonstrated a gadget by means of which he made people disappear.

Today Harold J. W. Raphael, director of Modern Traders, Ltd., of London, showed a small group of news men a similar apparatus. At first glance, the second device did not seem quite as effective as the first. All that Mr. Raphael made invisible was a radio set, a tin of cigarets, and a clock.

Mr. Raphael, whose machine was also invented by a Hungarian — Prof. Stephen Pribil — was considerably exercised over Prof. Gosztonyi's activities.

"If we find," he said, "that this man has infringed our patents, we shall institute proceedings immediately. We shall go after him to vigorously that you won't be able to see him at all."

Beyond saying that "a combination of concentration of certain light rays" were used and that "there are absolutely no mirrors" in the apparatus, Mr. Raphael declined to reveal the secrets of his magic.

Nobody ever is described as "considerably exercised" anymore. What a loss.

Harold J. W. Raphael leaves a few footprints in the historical record outside of this article. He had a legitimate patent on a razor, which was the product that Modern Traders, Ltd. vigorously hawked in the British papers. His connection with Pribil is a mystery, like so much else in this tale.

Did Gosztonyi steal Pribil's idea? Based on the tiny shreds of evidence left to us, I'd say a good case can be made that he either ripped off Pribil or he discovered who Pribil was imitating and brought out his own version. Compare the pictures in this article by A. L. White in the October 1936 issue of Modern Mechanix to the ones in the American Weekly article.

Gosztonyi used the identical chair trick as well.

In a demonstration of this machine recently the stage was set with a backdrop of wide red and white stripes. A chair, lifted from among the onlookers so that all could see that it was genuine, was placed in front of this conspicuous background. Then a young man — a very substantial young man — who had been walking around among the onlookers, stepped onto the stage and sat down in the chair. Soon he grew dim in appearance, became sort of thin vapor so that the striped backdrop was visible through the outlines of his body. Then he disappeared completely. But the chair remained, whole and firm, and the young man continued talking to the onlookers as an evidence of his presence. His disappearance, nevertheless, was to all intents and purposes so absolutely real that when the inventor called to the operator of the machine to bring the young man back to sight, one of the onlookers exclaimed: “But suppose you should ever fail to bring him back. What then?”

How was it done? Invisible rays.

"[I]t is an application of rays of invisible light. Mr. Gosztonyi says: “It is a combination of lights and shadows. . . . The machine produces rays of invisible light -- some rays of great intensity, some of minor intensity. They play one against the other.”

Pribil was included in the same article, and his explanation neatly tracked his rival's.

This is no illusion done by some magician, no trick of mirrors, it is asserted, but an actual performance of a new device which produces and projects what, for lack of a better name, may be called an “invisible ray.” The apparatus, itself, looks like a long tool box from which cords like telephone or electric cords extend. Lights are projected onto any object placed within the cabinet. The effects of disappearance and reappearance are obtained, it is explained, by synchronization of invisible rays.

Invisibility is produced by invisible rays. Of course. It would only be weird if the rays were visible.

Gosztonyi fades from the public record after this as an inventor. The idea was far too good to be abandoned, though. The next reports came from Italy in early 1937 and sounded like a rerun of 1936. "Prof. Mario Mancini, who makes people disappear by 'purely scientific principles,' insisted today he was not a magician— and '"I do not use mirrors.'" The headline over the article read "Magician Has Box to Makes Aids Disappear" (1937-03-02 Indianapolis News p.B-13, credited to the Associated Press). Mancini, amazingly, actually was a professor, unlike the courtesy titles of "Prof." bestowed on both Pribil and Gosztonyi, purportedly a former professor of physics at Milan's Breda Academy. (Milan does not seem to have a Breda Academy. It has a Brera Academy, but that's an art gallery, part of the Academy of Fine Arts. A physics professor there is not impossible, but the background is already shaky. Or seems so to modern eyes. Nobody expected newspapers to fact check in those days.) The rest sounds very familiar.

A huge wooden box, of practically cubical shape, the sides of which were about eight feet long, occupied nearly half the drawing room where the thirty-three-year-old professor held his demonstration.

The side toward the observer apparently was open but in reality was closed by a sheet of transparent glass....

The professor pressed a button illuminating the box inside. Simultaneously there was s distinct buzzing sound.

After a few moments the outlines of the two women and chairs became more and more indistinct, until they disappeared completely.

How did it work? The obvious way. It "nullifies the rays reflected by opaque bodies."

The newspapers took this third man up to the plate less seriously than the first two. In December of 1937, the NEA Service sent out a squib on its syndicated wire that was, as the Saturday Evening Post feature had it, the perfect squelch.

The signor must've gotten in front of the beam himself because he hasn't been heard nor seen since.

Austrians got into the spirit of things as well. A 1947 article from a Scottish newspaper (1947-09-10 Dundee Evening Telegraph) said that "An Austrian inventor has succeeded by making himself disappear by means of an electrical ray." The article remembered Pribil's 1936 demonstrations in London and added that "A year later, three Viennese engineers using three kinds of rays (allied to X-rays) had a similar success."

Pribil showed the advantage of being first. As late as 1939, the St. Louis Post ran yet another illustrated article on him, with yet another wildly different explanation of his process.

[H]e produced rays which changed the oscillations of light rays - 400,000 to 800,000 billion a second - so that these oscillations were out of the range of the retina of the human eye.

The newspaper is honest enough to note that "A prominent St. Louis scientist, informed of this explanation, expressed skepticism." Quite rightly.

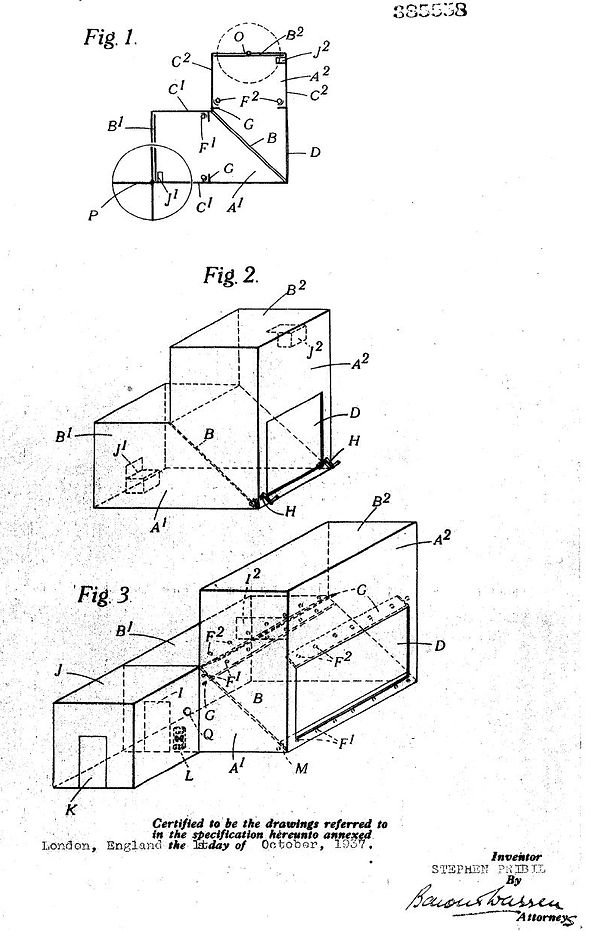

Although it appeared in no newspapers, Pribil thoughtfully gave us all the details when he finally patented his invention. It shows up in the database as Canadian patent #385558, granted December 12, 1939, but filed in London on October 1, 1937. The title gives the whole show away. It reads Optical Illusion Apparatus. (An earlier, and very similar, patent was filed in London on June 30, 1936 (just before the contretemps with Gosztonyi: makes me think he knew what was coming) and appeared as Canadian patent #376510, granted September 13, 1938 and titled Display Apparatus. The wording of the purpose of the apparatus is clearer in the later patent, however, so I'll quote that.)

The first question you should have by this point must inevitably be: "was it done with mirrors?" The only fair answer is: "yes and no." Unsatisfying? Well, the secrets behind most magician's tricks are. Just enough no is involved so that all the deniers could honestly claim that no mirrors were involved. The trick is one of definition. The ordinary definition of a mirror is a piece of glass coated with a dark backing to reflect light. Generations of magicians already knew that the same principle could be achieved with a bare piece of glass. Any properly constructed black background, the inside of a box, say, could serve as the reflector. Angle the glass at 45 degrees and objects could be made to fade away as the light source changes. The diagram in the patent shows the sides of the box, the parts that the audience couldn't see.

The accompanying explanation, taken verbatim from the patent in all its barely readable English, makes it clear that the trick is simply a variation of classic illusions like Pepper's Ghost.

The present invention relates to an apparatus by means of which persons, objects or the like normally visible on a stage, in some exhibition space or in a portable apparatus, all of which have surroundings which remain visible, can be made gradually invisible and again visible, that is to say, the persons, objects or the like appear to disappear and then reappear.

The invention is based on the principle of darkening a compartment in which the person or objects to be made intermittently invisible are located and into which the observer can see, and at the same time or nearly the same time of illuminating a second exactly similar compartment but masked from the observer and of producing exactly in place of the darkened compartment an image of this second compartment as also of the internal arrangement of the same. ...

During the controlling of the light sources, no perceptible darkening of the space occupied by these persons or objects takes place from the point of view of an observer, nor is there any change of position of the persons or objects and their surroundings, nor any mechanical masking of them, but the process of becoming visible or invisible takes place in the space remaining illuminated approximately in the way it would take place with a gradual materialization and de-materialization of bodies.

Pribil - and Gosztonyi for that matter - kept saying they hoped to sell their invention for the stage. Hyping the old and tired with a dollop of modern science got them in the papers in a way no acknowledged magician ever could.

With one exception. Joseph Dunninger might have been the premier magician of the age, the successor to Houdini. Anything he said was news. On April 13, 1939 he made the front page of the Detroit Free Press under the headline, "Magician to Show Navy How to Make Fleet Invisible."

The battleship, he said, would be invisible until it approached within a half mile of the enemy, no matter how powerful the glasses they train on it. Any ship could be outfitted with the device at the comparatively negligible cost of about $3,000 or $4,000 a ship, he declared.

"Absolutely no mirrors are used," he said.

A sucker is born every minute.

Although Dunninger said he was going to Washington the next week, it's not clear if he ever actually met with officials. Even a New Yorker casual in October was vague about his movements. Not until November did a follow-up story appear (1939-11-30 Hazelton [PA] Plain Speaker).

![1939-11-30 Hazelton [PA] Plain Speaker](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/3a61d0_1ea730b1aa3b4082b5a6c36156271961~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_442,h_768,al_c,q_80,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/1939-11-30%20Hazelton%20%5BPA%5D%20Plain%20Speaker%201.jpg)

Dunninger later claimed he gave his idea to the government as a gift but there's no evidence that it was ever tried, even for a rowboat. The U.S. was not yet in the war when he shot his mouth off to the press; he was conspicuously quiet about it after Pearl Harbor.

Nothing as wonderful as an invisibility ray could escape the notice of other popular media. The Boris Karloff chiller called The Invisible Ray, put into production in mid-1935, has a plot, to use the term loosely, that has in it everything but an invisibility ray. Li'l Abner started an invisibility sequence in 1937 but that has Mammy Yokum becoming invisible by the mystic gestures of a swami.

More on point is the Myra North, Special Nurse sequence titled "The Invisible Man." Myra mostly stayed out of the hospital to battle the several zillion spies and saboteurs that infiltrated newspaper comics (and comic books and mysteries and...) before and during WWII. In December 1939, shortly after Dunninger's invisibility ray was back in the news, Myra was bedeviled by the devilish "Hyster," who always knows where to find an evil scientist and his new discovery.

![1939-12-03 Casper [WY] Star-Tribune Myra North](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/3a61d0_0f99a410d4a944beaf82e5bb74a63101~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_592,h_822,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/1939-12-03%20Casper%20%5BWY%5D%20Star-Tribune%2037%20M.jpg)

If only it were that easy.

Postscript. I make the heretical argument that the vast majority of ideas that are credited to science fiction writers have been picked up from nonfiction accounts in newspapers, magazines, scientific journals, and whatever the latest technology is. Invisibility rays are a good example. I have even better evidence now, thanks to Julián Puga, who made a wonderful find referencing Pribil. The lead story in the January 1938 issue of Doc Savage was "The Living-Fire Menace," with Harold A. Davis subbing in for Lester Dent. On DocSavage.org, fan Thomas Fortenberry noted all the science-fictional gadgets that Doc employs. "Here Doc has 2-way televisors in every car and plane; films his reception room 24/7, and employs projectors of “invisible rays” so that no one can see him. Renny is said to be stunned by Doc’s invention of an insta-matic camera that shoots out developed pictures a la a later polaroid.

Wait, "invisible rays?" Yep. Julián sent me the relevant paragraph.

And while becoming invisible was not commonplace, it was something that had been done before. The switches he had operated had released a series of short high-powered light waves, known as invisible rays. As those rays struck a human being, that human gradually vanished simply because the eye could not distinguish it when penetrated by the speeding beams. Doc had not invented the process; that had been done by Stephan Pribil, a Hungarian scientist. But the bronze man had improved it, so that invisibility came almost immediately.

The casual reference to Pribil indicates how extensive the American publicity must have been. Davis could easily have attributed the rays to Doc's genius but knew that the recent ubiquity of Pribil in the news would still be in readers' heads. Better to have him improve on the original and mark his superiority without a smudge on his character. It's blather, but it's great blather.

March 22, 2020

Postscript, March 25, 2021